Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge

I close my eyes and see him windmilling his arms as he plummets from

the Mystic Tobin Bridge, to prove me wrong, to show me he was good,

to atone for sins like seeds in the lopsided apple of his heart, but mostly

to escape from me in the back of his cab, a Puerto Rican lawyer in a suit and tie.

I hated the 111 bus, sweltering in my suit and tie with the crowd in the aisle,

waiting to hit a bump on the Mystic Tobin Bridge so my head would finally

burst through the ceiling like a giraffe on a circus train. I hated the 111 bus

after eviction day in Chelsea District Court, translating the landlords and judges

into Spanish so the tenants knew they had to stuff their clothing into garbage

bags and steal away again, away from the 40-watt squint that followed them

everywhere, that followed me because I stood beside them in court. I would

daydream in the humidity of the bus, a basketball hero, flipping the balled-up

pages of the law into the wastebasket at the office as the legal aid lawyers

chanted my name. I hated the 111 bus. I had to take a taxicab that day.

What the hell you doing here? said the driver of the cab to me in my suit

and tie. You gotta be careful in this neighborhood. There’s a lotta Josés

around here. The driver’s great-grandfather staggered off a boat so his

great-grandson could one day drive me across the Mystic Tobin Bridge,

but there was no room in the taxi for chalk and a blackboard. He could

hear the sawing of my breath as I leaned into his ear, past the bulletproof

barricade somehow missing, and said: I’m a José. I could see the 40-watt

squint in his rear view mirror. I’m Puerto Rican, I said. It was exactly

5 PM, and we were stuck in traffic in a taxi on the Mystic Tobin Bridge.

The driver stammered his own West Side Story without the ballet,

how a Puerto Rican gang stole his cousin’s wallet years ago. You think

I’m gonna rob you? I said, in my suit and tie, close enough now to tickle

his ear with the mouth of a revolver. I could hear the sawing of his breath.

He still wanted to know what I was doing there. I’m a lawyer. I go to court

with all the Josés, I said. Stalled traffic steamed around us, the breath

of cattle in the winter air. Where you going for the holidays? the driver said.

I thought about Christmas Eve in court, eviction orders flying from the judge’s

bench when tenants without legal aid lawyers, or children old enough to translate

the English of the summons, did not answer to their names. Every year, the legal

aid lawyers told the joke about The Christmas Defense: Your Honor, it’s Christmas!

I said to the driver: I will be spending Christmas right here with my fellow Josés.

The driver shouted: What do you want me to do? Get out of this cab and jump off

the bridge? We both knew what he meant. We both knew about Chuck Stuart,

the last man to jump off the Mystic Tobin Bridge. Everybody knew how Chuck

drove his wife to Mission Hill after birthing classes, the flash and pop in the dark

when he shot her in the head and himself in the belly. Everybody knew how

he conjured a Black carjacker on the crackling call to 911 the way the Mercury

Theater on the Air conjured Martians in New Jersey on the radio half a century

before. Everybody knew how a hundred cops pounded on door after door

in the projects of Mission Hill, locking a Black man in a cage for the world to see

like the last of his tribe on exhibit at the World’s Fair. Everybody knew how

Chuck would have escaped, cashing the insurance check to drive away with

a new Nissan, but for his brother’s confession, the accomplice throwing

the Gucci bag with makeup, the wedding rings and the gun off the Dizzy Bridge

in Revere. Everybody knew how Chuck parked his new car on the lower deck,

left a note and launched himself deep into the black water, how the cops

hauled his body from the river by lunchtime, when I walked into the office

to tell the secretary: Chuck Stuart just jumped off the Mystic Tobin Bridge.

I said nothing to the driver. I almost nodded yes in the rear view mirror. I confess,

for a flash, I wanted him to jump. The driver, the cops, the landlords, the judges

all wanted us to jump off the Mystic Tobin Bridge, all wanted us to sprout gills

like movie monsters so we could paddle underwater back to the islands, down

into the weeds and mud at the bottom, past the fish-plucked rib cages of the dead,

the rusty revolvers of a thousand crimes unsolved, the wedding rings of marriages

gone bad, till we washed up onshore in a tangle of seaweed, gasping for air.

Last night, still more landed here, clothing stuffed in garbage bags, to flee the god

of hurricanes flinging their houses into the sky or the god of hunger slipping

his knife between the ribs, not a dark tide like the tide of the Mystic River, but

builders of bridges. You can walk across the bridges they build. Or you can jump.

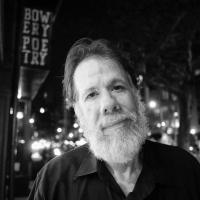

Espada, Martín. "Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge." Floaters, W.W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Rights: Martín Espada; W.W. Norton & Company